Gold has at all times been considered the best of testimonies of good faith

Rafael Sabatini

People have always wanted and needed to transact with each other. In the beginning, it was barter. The concept of “I’ll swap you these fish for some firewood”, or such like. While it worked, it was clearly very restrictive and relied on two people needing a direct exchange. What was really needed was a trusted store of value that could be used as payment for goods and services, over and above direct barter. It started with sea-shells and stones that were used as currency, things that could be recognised and counted to account for transactions, moved to commodities like salt and then ultimately to Gold and Silver. The English language even has some surviving remnants of this history with ‘shell out’, as a slang term to pay for something and ‘salary’ as monthly payment for work, originating from salt.

Gold (and silver) ultimately became the real units of currency upon which world trade is based. Historically they have replaced all other forms of currency in civilisation because they are durable and not easy to replicate, so future value is relatively assured. Gold is naturally scarce, so perfect as representing value – that ancient alchemy was about trying to turn lead into gold is no coincidence and the entire gold of the world would fit into a tennis court-sized cube. Gold especially has a reputation for not tarnishing or rusting, and is even resistant to some strong acids, meaning that as far as a medium of exchange goes there is nothing, quite literally, “as good as gold”. It’s also infinitely divisible in weight as a currency unit and an ounce of pure gold in the African desert is identical and therefore worth exactly the same as an ounce of pure gold in London, making it perfect for international trade.

Gold is, essentially, the perfect item for stored savings and to be used as a medium of exchange with another party as and when required. You can take a gold coin as payment, bury it in the garden for 2,000 years and it will remain as shiny, perfect and representative of it’s true value as ever. The 2,000 years may seem extreme, yet hoards of this age of gold coins turn up surprisingly often and are worth an awful lot of money. Compare this to if the coins were made of a cheaper metal, they’d rust and corrode, often disappearing completely.

It started with exchanging pieces of gold and silver, but that was impractical so people learnt to melt them down into regular sizes, or weights, then into rounded discs called coins, or ‘specie’. Paper money only came into being in the first place as a substitute for the practice of using physical gold and silver in transactions and the trouble of getting your shovel out to bury it then dig it up, perhaps. What happened was that people deposited their gold with a bank, and then the bank would issue them with a promissory note, or notes for the value of their gold. People could then use their notes to buy goods and the person receiving the note knew they now owned the amount of precious metal stated on the note.

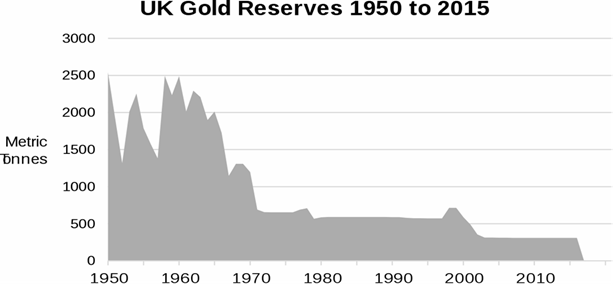

The real problems started occurring when people – normally banks, governments and forgers, began issuing extra currency backed by the same amount of precious metal, and, in 1971, the last historic link between gold and worldwide currency was removed by the USA, when they removed the link that 1 ounce of gold could be exchanged for 35 dollars and vice-versa. Up to this time, gold had a fixed value in terms of world trade.

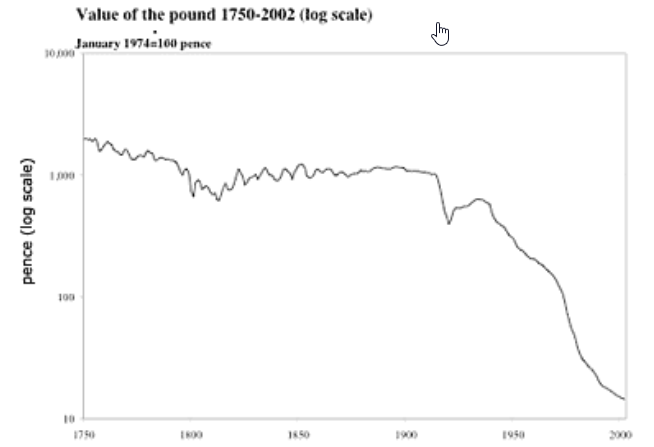

To give you an example of how that paper you have in your wallet, or digital bits on your banking homepage screen have become distended from the real money it once represented, just think of this – A British Pound Sterling was once worth exactly what the words say – A pound in weight of Sterling silver. As of the end of August, 2020, the same pound of sterling silver is valued at £282, or $376. That is 0,0035% of its original value.

It is also worth noting here that Gold is a purer representative of true wealth than silver. Although both metals have been heavily used throughout history as currency and to represent wealth, Gold has few uses apart from as money, whereas Silver is a heavily used industrial commodity and that can affect its price and desirability outside of any investment considerations. For example, back in 2007, some commentators were convinced that the rise of digital photography and the resultant downturn in traditional photography would result in a massive decrease in demand for silver, affecting the price negatively as a result. This may or may not have occurred, as silver did experience some major shifts in price versus fiat currency in the period 2007-2020. However, silver has many, many other uses, including electrical components and such uses are only increasing as technology increases.

To put the importance of gold in perspective, imagine you time-travelled back to 1910, almost anywhere in the world. The people were transacting with gold and silver and there was even something called a ‘Gold Standard’, for international trade. In practice, this meant that gold physically moved between countries according to the balance of trade between those countries. If you had a deficit, you lost gold, if you had a surplus you gained gold. In other words, a nation state was just a larger version of how we all run our own household finances. Now, imagine that as part of your time-travelling visit, you tried to pay for something. Having first noted that there was no card terminal for you to tap or even enter your PIN on, no mobile payments, you tried using the modern equivalents of some of the coins in circulation. People may have looked at your legal tender dubiously, noting they were made of steel, nickel or paper and therefore not worth anything like the coins they were used to – the silver shillings or dollars, the gold sovereigns, all with real intrinsic value. Who was more financially aware, them or us?