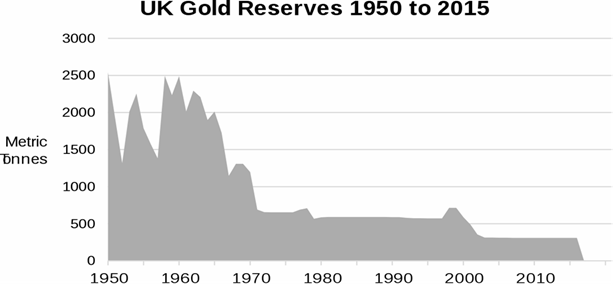

Once governments got you used to the concept of using just one currency in your everyday transactions and got you used to the trust that they were looking after your gold – they began loaning it out and selling it off, often without your knowledge or consent.

(Chart: source: Wikipedia By Tsange – CC BY-SA 4.0)

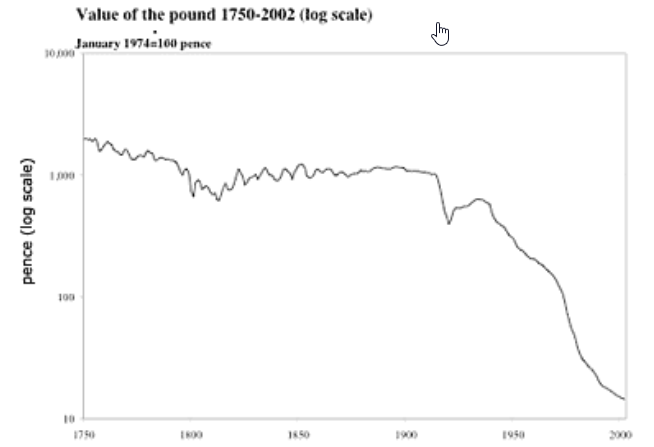

Looking at the chart, it’s easy to see the UK gold reserves have declined massively, especially in the 1960s – leading to the famous ‘Pound in your Pocket’ speech by Prime Minister Harold Wilson in 1967, trying to assuage voters that their pound was still worth a pound, as the value plunged against other currencies. A pound of what, Harold? In 1999, the UK decided to sell off over half the nations’ remaining gold reserves, some 400 tonnes. At the time, gold was at the end of a major 20-year bear market, and the price was at an all-time low, a price last seen in the 1970s. The Bank of England, the custodian of the countries’ gold reserves, insists that it was never consulted in the decision, and some leaks, in fact, suggest that many of their staff vigorously opposed the move. They claim that Her Majesty’s Treasury and them alone made the decision. At the time, the Chancellor of the Exchequer was a Mr. Gordon “Golden” Brown, who subsequently became Prime Minister.

Even worse, the huge gold sales and auctions were publicly announced well in advance, thus giving gold dealers the chance to prepare for the glut of gold that was about to be released onto the market, and force the price down still further as a result. The normal strategy is to keep intended government gold sales quiet, then simply conduct the sales on the open market, obtaining the best prices possible, then announce the results afterward.

Why might a government decide to sell off one of the main assets of its people at the lowest price possible? There were rumours and accusations that the gold was sold to prevent top Hedge Funds who had got it wrong gambling on the price of gold from going bust and destroying the worldwide economy, among others.

Regardless of the truth of the rumours, 1999-2002 has subsequently been proved to have been exactly the right time to start buying gold, not selling it; in fact, the value of the gold sold by the UK has risen by over ten billion dollars since that time. This period in gold price history is now referred to as ‘The Brown Bottom.’