Hawick provides a clear case study of how a small industrial town once integrated into Britain’s productive and financial system — and what remains after that integration dissolves.

This was not a peripheral settlement. Hawick was deliberately built and connected because it produced. Its Georgian and Victorian architecture reflects capital deployed with confidence: mills, commercial streets, banks, clubs, and river infrastructure designed to serve output rather than appearance.

The town’s economic logic remains visible. Even after industrial contraction, the structure of production, finance, and circulation can still be read in stone and layout.

Hawick was once a mainline railway stop, linking Scotland through England to London. Such connectivity followed volume and output, not policy ambition. The railway’s removal was not the cause of decline but confirmation of it. As production diminished and capital withdrew, infrastructure followed.

Infrastructure does not fail first. It responds to capital flow.

Scottish Banknotes and Residual Issuing Power

Scotland remains one of the few developed economies where private commercial banks issue circulating currency.

These notes are denominated in sterling and fully backed by Bank of England reserves, but the issuing authority remains with individual banks. This is a surviving feature of an earlier monetary system in which money issuance was tied to trade-embedded institutions rather than centralised state monopoly.

The arrangement reflects a period when money followed reputation, settlement discipline, and local credibility. The notes are not symbolic. They are operational remnants of a decentralised monetary structure.

Savings Banks and Capital Preservation

Founded in 1815, Hawick Savings Bank was a trustee savings bank, not a growth institution.

Its purpose was capital preservation, not expansion. In towns with cyclical income and narrow margins, security mattered more than yield. Savings banks formalised thrift, deferred consumption, and custodial trust.

The language carved into stone — trustee, security, continuity — reflects a financial culture focused on endurance rather than leverage.

Production created surplus. Surplus required safekeeping. Safekeeping required trust.

Physical Cash and Risk Management

The night safe illustrates how money once moved.

Before electronic settlement, cash accumulation was a daily operational risk. Businesses deposited takings after hours. Banks collected later. Risk was managed mechanically.

Design prioritised security over convenience. Money was earned, counted, deposited, and reconciled. Responsibility was explicit.

Automation and Declining Permanence

The ATM hut reflects a later phase: access replacing custody.

Banking shifted from deposit to withdrawal, from relationship to convenience, from institutions to machines. This infrastructure expanded rapidly — and is now quietly retreating.

The hut remains not because it is valued, but because removal costs exceed benefit. It was never designed for permanence.

From Local Production to Imperial Circulation

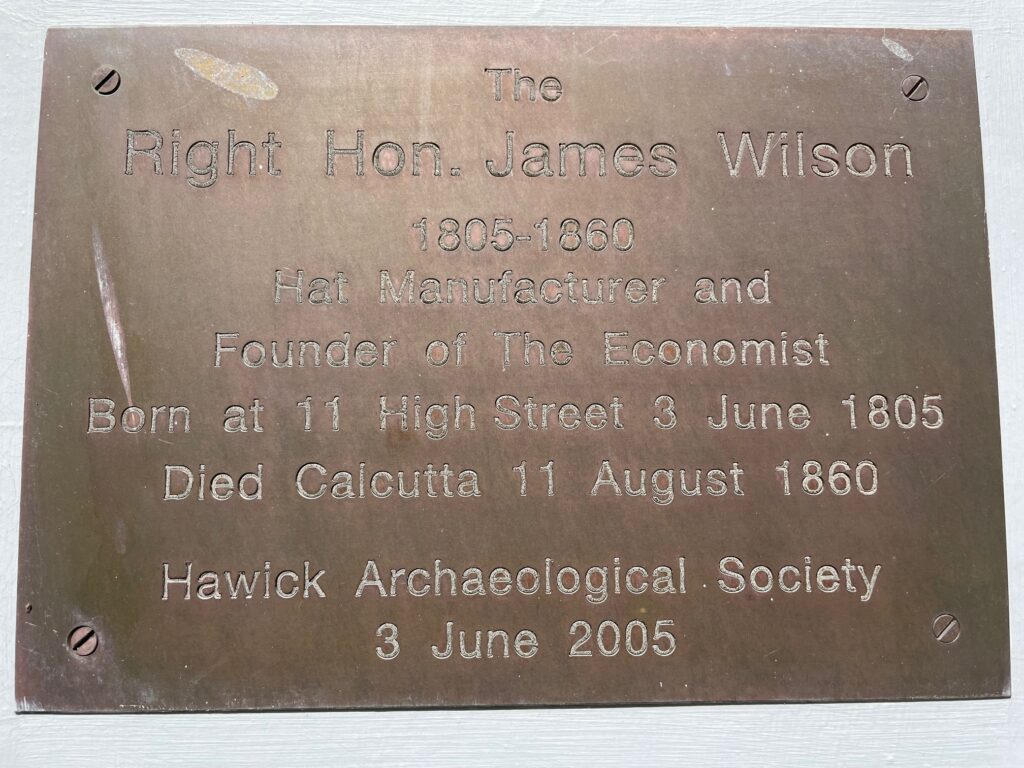

James Wilson, born in Hawick and later active in Calcutta, exemplifies nineteenth-century British economic expansion.

Manufacturing surplus drove wider markets. Those markets required stable currency, predictable rules, and financial commentary. Calcutta was a financial hub of imperial trade.

Hawick was not peripheral to empire. It contributed to it.

Clubs as Economic Infrastructure

Political and commercial clubs functioned as working institutions. Trade, shipping, currency, and risk were discussed practically.

Empire was not ideological. It was operational.

Border Economies and Mobility

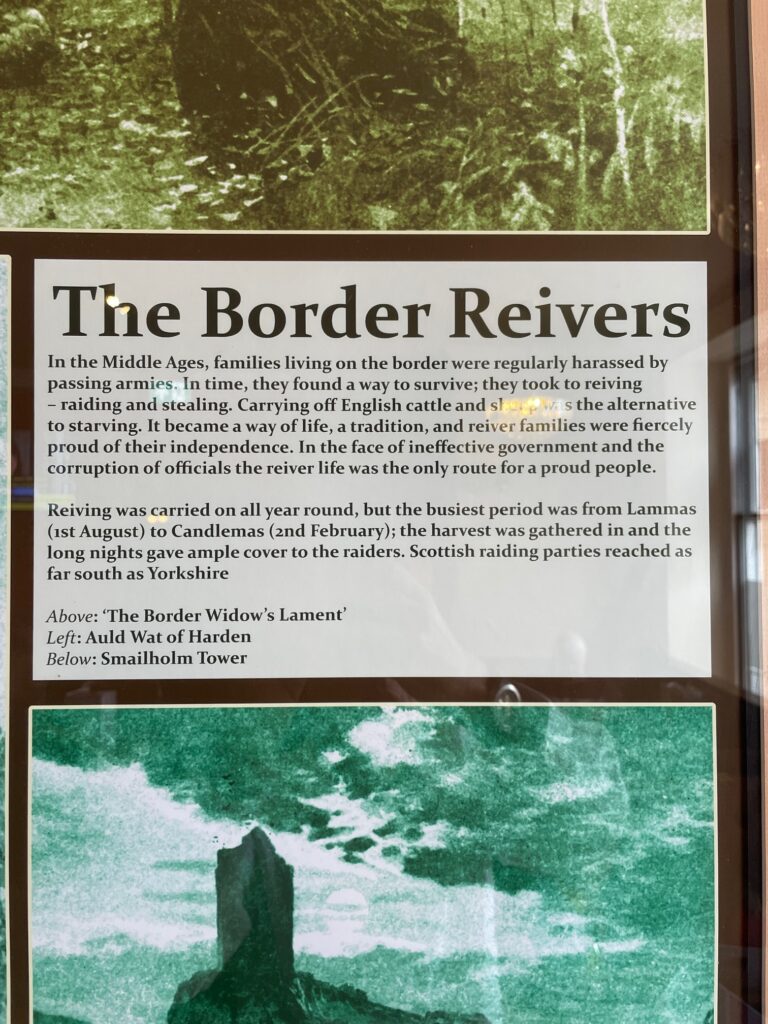

The Borders were historically unstable economic zones. Authority was weak, agriculture marginal, and mobility essential.

The Border Reivers were an adaptive response to pressure. When systems failed to sustain life, people reorganised or moved.

This pattern recurs across economic history.

Population Loss as Signal

Hawick’s population decline was gradual but decisive. Over time, opportunity narrowed relative to other locations.

This was economic sorting. People leave when reward structures weaken. The process is incremental and quiet.

Depopulation follows capital out.

Closing

Hawick demonstrates a basic relationship modern planning often misreads.

Money once followed production. Savings followed discipline. Movement followed pressure. When those links weakened, adaptation followed.

There is periodic discussion of restoring a rail link to Edinburgh. Such a connection would likely bring commuters and property demand. It would not restore locally anchored production.

A commuter economy changes function, not purpose.

The buildings remain.

The systems do not.

What survives is evidence.

Epilogue: Hard Money and Capital Anchors

Hawick’s most successful period coincided with a hard-money regime.

Under hard money, capital allocation was constrained. Credit followed production because it had to. Expansion required output, settlement discipline, and balance. Towns that produced attracted capital. Towns that did not, did not grow.

Hawick met those conditions. Manufacturing anchored trade. Savings accumulated slowly. Banking focused on custody rather than promotion.

The shift to soft money changed the equation.

Once currency became elastic and credit centralised, capital no longer required local production to justify movement. Scale, abstraction, and financial gravity replaced output as the primary attractors. Small industrial towns were not dismantled; they were bypassed.

Infrastructure withdrawal, banking contraction, and population loss followed.

Hard money rewarded Hawick because it produced.

Soft money ignored it because it no longer needed to.

That distinction matters.

As monetary systems again strain under debt, expansion, and declining trust, interest in tangible anchors inevitably returns: production, commodities, settlement reality.

Hawick does not offer a model to recreate.

It offers a reference point for what worked — and under what monetary conditions.

Hard money enforced reality.

Soft money suspended it.

The outcome is visible.

Leave a Reply